Have you ever wondered why some songs sound so heartbreaking and sad? There are many factors that affect a song’s vibe, like the lyrics, song structure, and chord progressions. Using chord progressions in minor keys is a surefire recipe for crafting a powerful, emotional experience for the listeners.

Depending on how you use them, these chord sequences can sound dark, unsettling, mysterious, sorrowful, and poignant. So, whether you’re looking to write songs, cover songs, or improve your guitar skills, you should have a bunch of popular minor chord progressions under your belt.

I’ve shared many of them below, from simple to complex. Understanding and learning to play these progressions will help you add several deeply emotional and powerful tunes to your repertoire. Scroll down to the bottom of the list if you want to take a quick look at the theory on minor chords and scales. Or you can jump straight to the progressions below.

Minor Chord Progressions Every Guitarist and Songwriter Should Know

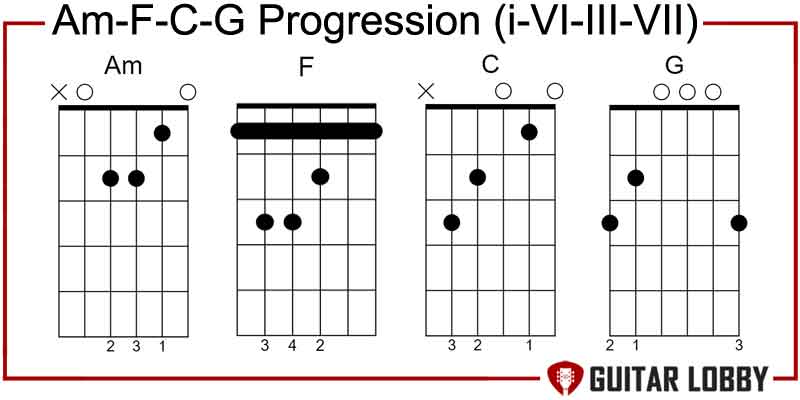

1. Am – F – C – G Progression i – VI – III – VII

Let’s kick off the list with one of the easiest and most common minor chord progressions out there: i – VI – III – VII. In the key of A minor, this sequence would look like Am – F – C – G. This progression is great at lending a somber vibe to the song, especially since it starts with a minor chord. But the fact that it has three major chords also makes it pretty versatile. It can go from sounding melancholic to dead serious based on the context. It’s also used by songwriters to create an upbeat track with a powerful lyrical message.

Those who aren’t quite at grips with playing F as a barre chord or having trouble transitioning from F to C can try this: place the index finger on the 1st fret of the 2nd string and then use the ring and the pinky finger to play the 3rd fret of the 5th and 4th strings, respectively. This hybrid way to play the F chord helps transition to the C chord because of the same ring finger position. If you want to learn the progression without any barre chords getting the way, you could try it in this sequence: Em – C – G – D.

Quick trivia: the Am – F – C – G and the hugely popular major progression C – G – Am – F have the same chords but sound nothing alike. This is because Am-F-C-G starts on a minor chord. It changes the feeling, making the progression darker and more emotional.

Once you’ve mastered the basic progression, you could try spicing it up by playing it as Amadd9-Fadd9-Cadd9-G.

Popular Songs That Use This Progression: “Save Tonight” (Eagle Eye Cherry), “21 Guns” (Green Day), “Fall For Youl” (Second Hand Serenade).

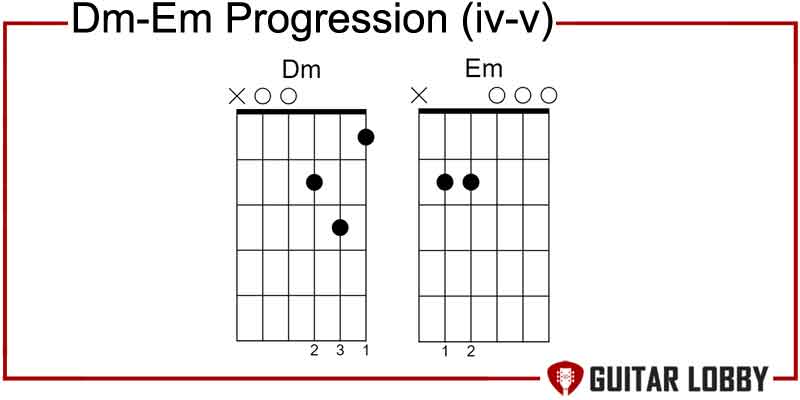

2. Dm – Em Progression iv – v

Now, who would use a two-chord progression, that too with only minor chords, to write songs? Turns out, quite a few indie and alt-rock bands use unusual sequences like iv-v to add a distinctive flavor to their tunes.

The most well-known track that uses this progression is “505” by the Arctic Monkeys. It’s also the easiest guitar tune in the alt-rock band’s catalog. They use Dm – Em progression, where both are open chords and quite beginner-friendly.

The only catch is switching from D minor to E minor. Start by making the D minor chord shape (pretty straightforward), and then move your index finger to the 2nd fret of the 5th string and shift the middle finger to the same fret of the 4th string. Next, release the ring finger, and you’ve got an E minor chord. Now move back to Dm by shifting the middle and ring finger down and then releasing the index finger.

The fascinating part, and quite frankly still shrouded in mystery, is the song’s key. Why do I say that? Because the key of D minor doesn’t have an E minor chord and vice versa. Some say it’s in D Dorian, while others think it’s in the key of D minor. The jury is still out.

Popular Songs That Use This Progression: “505” (Arctic Monkeys).

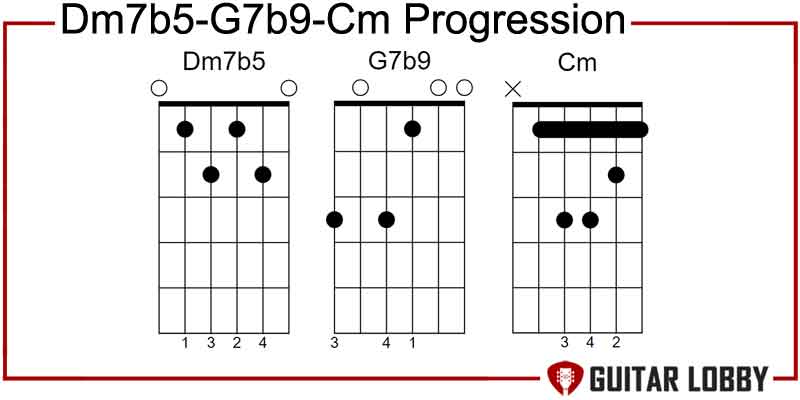

3. Dm7b5 – G7 – CminMaj7 Progression iim7b5 – V7b9 – i

The 2-5-1 progression is a prominent chord sequence in the world of jazz music where it’s played both in major as well as minor key. Plenty of iconic jazz songs have used this progression, often in C major scale with Dm-G-C progression or Dm7-G7-Cmaj7. However, a minor 2-5-1 chord sequence would be in a minor key, like C minor or F minor.

In a minor key, a 2-5-1 turns into iim7b5 – V7b9 – i. So, in the key of C minor, your sequence would look something like this: Dm7b5 – G7b9 – Cm. And in the case of F minor, it’ll become Gm7b5 – C7b9 – Fm. However, the ‘i’ chord is usually played as a minor, major 7th chord, or CminMaj7.

Now, these aren’t your standard chords and would take time to perfect. But learning the entire sequence is a building block to playing jazz melodies and soloing in minor keys. The easiest way to improvise over this progression is to use the notes from the C harmonic minor scale.

For the uninitiated, the C harmonic minor scale has the following notes: CminMaj7 – Dm7b5 – EbMaj7#5 – Fmin7 – G7 – AbMaj7 – Bdim7. Think of it as a shortcut or a starting point to soloing over this progression. You can always explore other ways to improvise over each chord, like playing D Locrian mode over the Dm7b5 chord.

Popular Songs That Use This Progression: “Autumn Leaves” (John Denver), “Black Orpheus” (Luiz Bonza), and “Blue Bossa” (Joe Henderson), “Along Came Betty” (Art Blakey).

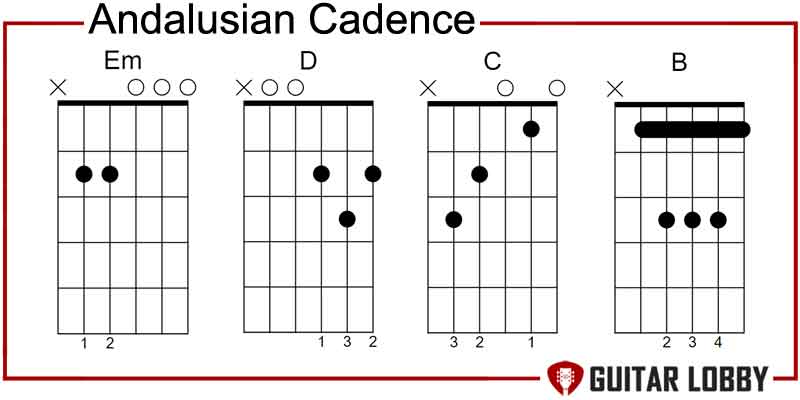

4. Andalusian Cadence

Also known as the flamenco progression, the Andalusian Cadence has made its way into many other genres, including rock, jazz, metal, baroque, and pop. It’s a minor chord progression made up of four descending chords to create a beautiful walking effect. In a major scale, it goes: vi – V – IV – III, but in a minor key, it becomes i – bVII – bVI – V and back to i. If we apply it to the A minor scale, the sequence would look like: Am- G – F – E or Am – G7 – F – E; in D minor, it would be Dm – C – Bb- A.

What you’re doing here is moving down the notes of a minor scale before going back to I for the distinctive flamenco sound. Another way to look at it is starting on any minor chord, then going down two frets to a major chord, then jumping back a whole step, playing a major chord, and moving down one fret to play a major chord again. A minor chord followed by three major chords is what makes Andalusian Cadence so versatile.

There are so many variations of this sequence that you can explore once you’ve mastered the basics, like i – bVII – bVI – bVII. Here, instead of going from bVI – V, you move from bVI – bVII. This is a very common sequence in pop and rock, and you would have heard it in the unforgettable “Stairway to Heaven” by Led Zeppelin.

Popular Songs That Use This Progression: “Citizen Erased” (Muse), “Sultans of Swing” (Dire Straits), “China Girl” (David Bowie).

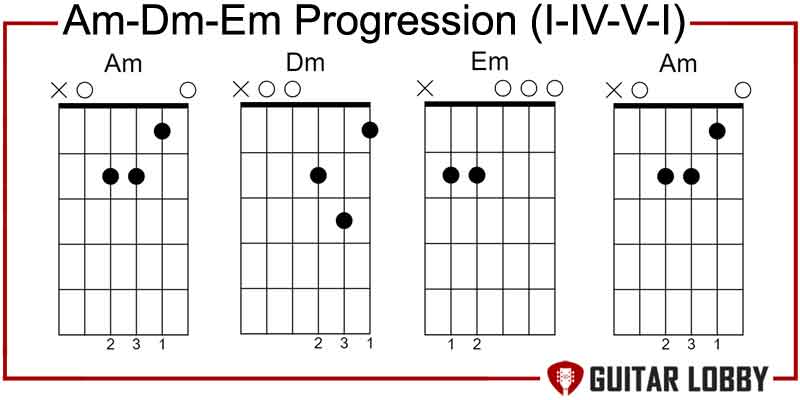

5. Am – Dm – Em Progression i – iv – v – i

If your goal is to write great songs, I highly recommend using popular chord progressions instead of avoiding them. Sure, we all want our music to sound unique, and an inventive chord sequence is a way to do that. But the classic chord progressions are common for a reason. They work! And you can always add your own spin to them. On that note, here’s another widely used minor chord progression that should be a part of your arsenal.

Progressions that revolve around the I, IV, and V chords are popular in major keys. And the same applies to minor keys. In the major key, these chords are played in the I – IV – V – I sequence but change to i – iv – v – i in a minor key.

The above sequence in D minor would look like Dm – Gm – Am – Dm, and in A minor, it would become Am – Dm – Em – Am. You can hear it in action in Bill Withers’ timeless hit “Ain’t No Sunshine.” This group of chords can also be heard in “Losing My Religion” by R.E.M but in a variation ending with the G chord or the major 7th chord of the A minor scale.

When you have Am, Dm, and Em in a progression, you’ll notice the Em chord sounds a bit meh. A tried and tested way to make this sequence even more beautiful is to play the 5th chord as a major chord instead. To see what difference ending on a major chord makes, play the progression with an E chord instead of Em. You’ll be surprised!

Popular Songs That Use This Progression: “Ain’t No Sunshine” (Bill Withers), “Losing My Religion” (R.E.M).

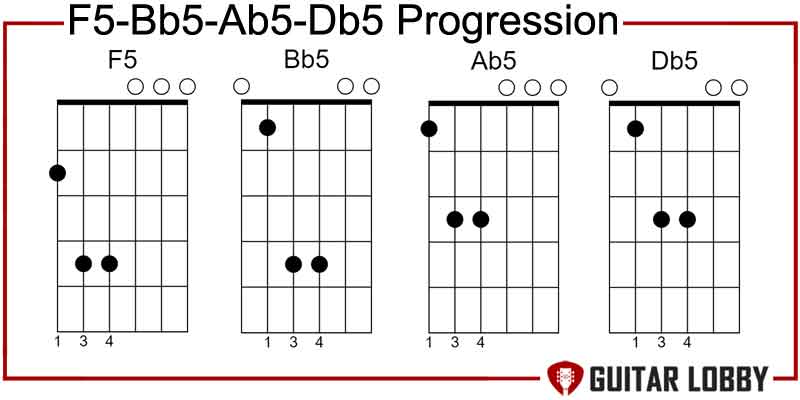

6. F5 – Bb5 – Ab5 – Db5 Progression i – iv – III – VI

The i – iv – III – VI progression has powered one of the catchiest and overplayed riffs of all time: Kurt Cobain’s punchy power chord belter in “Smells Like Teen Spirit.” It showcases the classic use of minor chord sequences in rock, where guitarists don’t use full chords and instead rely on power chords. Full harmonic chords sound gentler in comparison to the darker sound of minor chords with just roots and fifths minus the third intervals.

Let’s talk a bit more about the riff. It’s set in the key of F natural minor scale, which is made up of the following notes: F – G – Ab – Bb – C – Db – Eb. So an i – iv – III – VI progressions would start with an F minor, followed by a B-flat minor, then an A-flat, and finally a D-flat. But since we’re on the topic of Nirvana’s power chords-fuelled riff, the sequence would look like this: F5 – Bb5 – Ab5 – Db5.

Try the riff in both arrangements, playing it with full chords and then with power chords with some palm muting. Notice how heavy and aggressive the power chord progression sounds in comparison. Another reason why this progression sounds so unique is that it ends on the VI chord instead or v or Vth chord. As ending on the 5th chord sounds powerful when you return to the i chord, but it’s also quite predictable.

Popular Songs That Use This Progression: “Smells like Teen Spirit” (Nirvana).

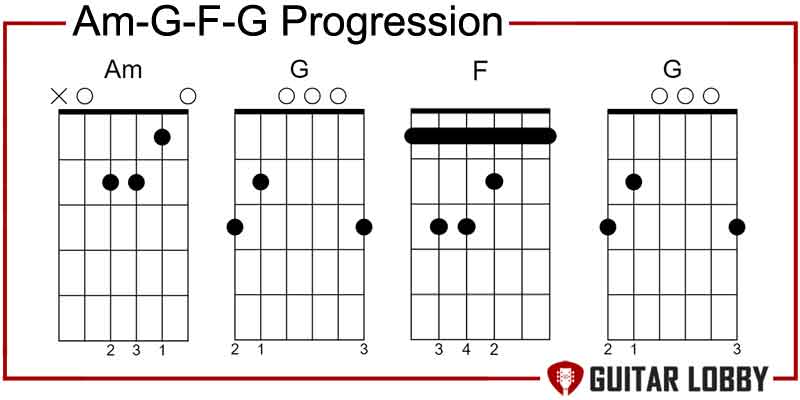

7. Am – G – F – G Progression i – bVII – bVI – bVII

I mentioned how Andalusian Cadence is the source of many common chord progressions, like this one. The i – bVII – bVI – bVII is a variation of the flamenco sequence, ending on bVII instead of the V chord. It still manages to come across as an impactful progression, relying on flat chords to build tension.

Let’s take the example of the A natural minor key to understand this sequence better. A natural minor key has the following chords: i – ii˚ – bIII – iv – v – bVI – bVII (we’ll get into it in a bit more detail in our theory section). The chords in A natural minor scale are: A – B – C – D – E – F – G. So, our chord progression becomes Am – G – F – G.

You can sample this chord combination in all sections of Bob Dylan’s “All Along the Watchtower” or the chorus of “Rolling in the Deep” by Adele. You can also hear it in “Somebody That I Used to Know” by Gotye, where the verses use i – bVII, and the chorus has the entire sequence.

Popular Songs That Use This Progression: “All Along the Watchtower” (Bob Dylan), “Rolling in the Deep” (Adele), “Somebody That I Used to Know” (Gotye), “In the Air Tonight” (Phil Collins).

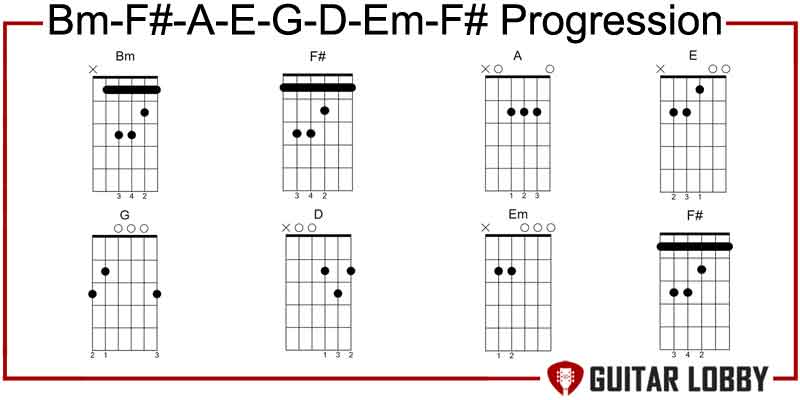

8. Bm – F# – A – E – G – D – Em – F# Progression i – V7 – VII – IV7 – VI – III – iv7 – v7

Here’s a longer and more complex variation of the Andalusian Cadence made famous by the legendary Eagles in their magnum opus “Hotel California.” Among other factors, the fascination and undying love for this tune is because of its harmonic complexity. Key changes, harmonic motifs, never-heard-before chord sequences – this song has it all.

There are two prominent chord progressions that make this song, one in the verse and the other in the chorus. The verse is where you can hear the i – V7 – VII – IV7 – VI -III – iv7 – v7 sequence. In the original song, this progression appears in the B minor, which is a great key to hone your barre chord-playing skills.

Now, let’s take a look at the chords that make up the B minor scale: B – C# – D – E – F# – G – A. The famous and unusual verse chord progression goes Bm – F# – A – E – G – D – Em – F#. Why I call it unusual is because it doesn’t stay in the same key. For instance, it features both E minor and E major in the progression.

I’ll not get too much into the specifics of how to play this progression. There are plenty of tutorials online to help you with that. But the gist is that it’s played on a 12-string guitar, with each chord getting a full measure except for G and D, which only get half a measure.

Popular Songs That Use This Progression: “Hotel California” (Eagles).

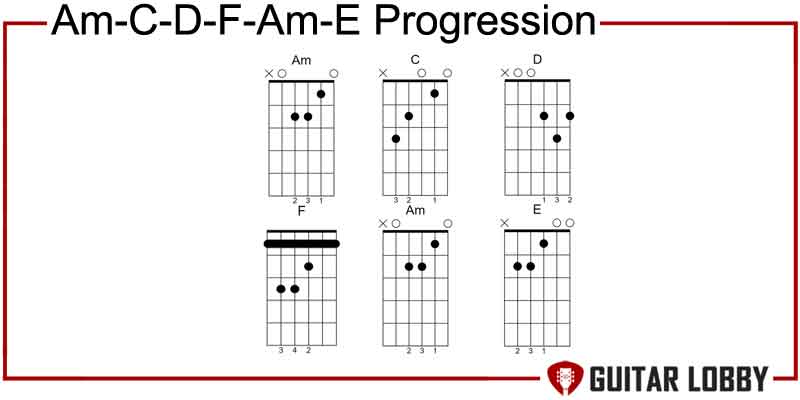

9. Am – C – D – F – Am – E Progression i – III – IV – VI – i – V – i – V

Since we’re on the topic of unusual but iconic minor chord progressions – here’s another fantastic one heard in the Animals’ massive hit ” House of the Rising Sun.” The 1964 folk-rock gem is set in the key of A minor with a main progression that looks like this: Am – C – D – F – Am – E or i – III – IV – VI – i – V – i – V.

Just to recap, the A minor key is made up of Am – Bdim – C – Dm – Em – F – G chords. So what is an E major chord and a D major chord doing in the same progression? Well, you’re looking at a mode mixture. What this essentially means is that there’s been some borrowing from parallel scales. Let’s break this down a little.

The A natural minor is the same as an A Aeolian mode, which is basically the sixth mode of the C major scale. Apart from the Aeolian mode, most minor key songs that revolve around the A minor also do a bit of borrowing from A Dorian. This is the second mode of the G major scale with the following notes: A – B – C – D – E – F# – G.

Songs also pick notes and chords from A harmonic minor, which is the same as A natural minor, except it raises the 7th degree by a semitone, making G go to a G#. This also changes the E minor chord to E major.

So there you have it! The D major chord in the Animals progression is, in all likelihood, lifted from the A Dorian mode and the E major from the A harmonic minor.

Popular Songs That Use This Progression: “House of the Rising Sun” (The Animals).

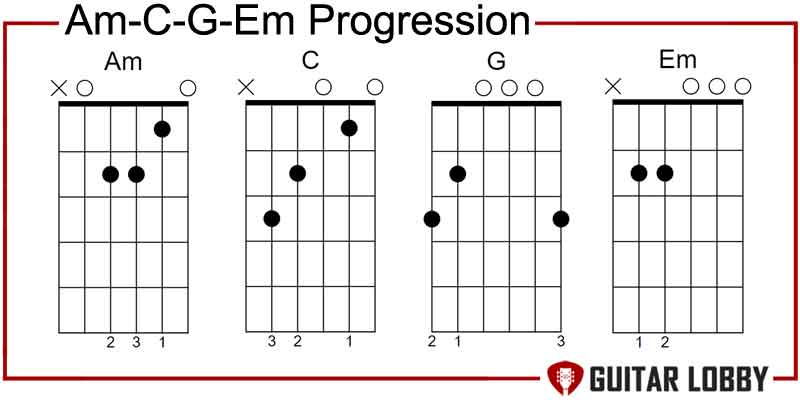

10. Am – C – G – Em Progression i – III – VII – v

There’s no modal interchange or borrowing happening in this chord sequence. As you can make out, it’s in the key of A minor, which contains the following chords: Am – Bdim – C – Dm – Em – F – G. So the progression Am – C – G – Em or i – III – VII – v has all the chords it needs right here in A minor key.

This is an interesting group of chords, and I am surprised that there aren’t many songs that use this. The best example that comes to mind is the arpeggiated riff in Metallica’s “Fade to Black.” It makes excellent use of the strong harmonies that the III chord and VII chord have to offer.

If you want to check how good it sounds without getting into arpeggios, just strum the chords as an open chord progression. The switch from Am to C chord is very smooth and clean and only requires you to move only your ring finger. Moving from C to G is slightly trickier.

Start by making a C chord shape, and then move your index and middle finger to the bottom two strings. Now, place the ring finger and pinky on the top two strings. Next, move from G to E minor chord by leaving your index finger in the same spot and shifting the middle finger to the 2nd fret of the 4th string. Now, play each chord for a full measure. Sounds awesome, doesn’t it?

Popular Songs That Use This Progression: “Fade to Black” (Metallica).

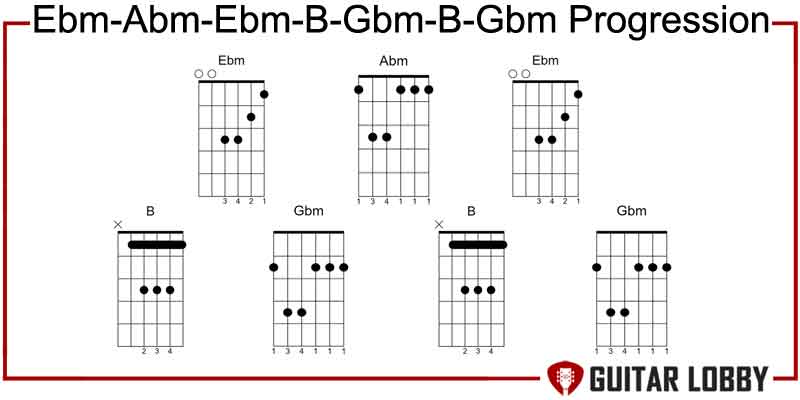

11. Ebm – Abm – Ebm – B – Gbm – B – Gbm Progression i – VII – i – VI – III – VI – III

The VI major chord is a kingpin in minor chord progressions. Things brighten up when you go from a suspenseful ‘i’ chord to the cherry ‘bVI’ chord. A longer version of I – bVI is in one of the most famous folk-rock songs, Simon and Garfunkel’s “The Sound of Silence.” The first part of the progression i – bVII – i sounds a bit sad, but the mood brightens when the chords change from i to bVI and bVI to bIII. In its entirety, the sequence strikes a wonderful balance between somber, dreamy, and wistful emotions.

The beautiful song is set in the Ebm or E flat minor key. That makes the chord sequence in question look something like this: Ebm – Abm – Ebm – B – Gbm – B – Gbm. Another and more commonly used way to play this song is with a capo on the 6th fret and with chords that are a part of the A minor key. The chord progression then becomes Am – G – Am – C – F – C – F.

If you’re a beginner, the full F barre chord shape might be challenging, especially with a capo on the 6th fret. In that case, you can swap it with any alternate F chord voicings you’ve learned.

Popular Songs That Use This Progression: “Sound of Silence” (Simon and Garfunkel).

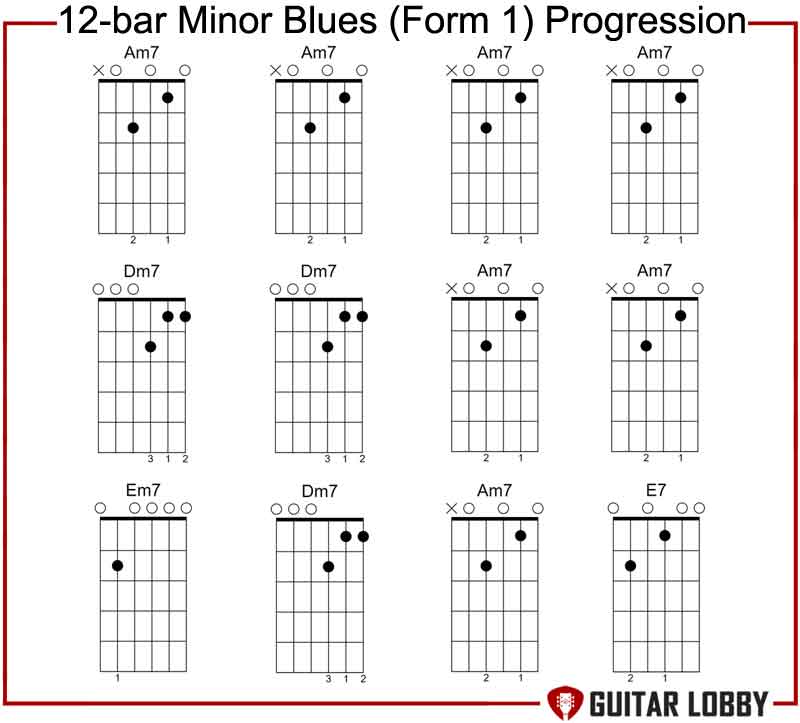

12. 12-bar Minor Blues (Form 1) Progression i – i – i – i – iv – iv – i – i – v – iv – i – V

The I, IV, and V chords are essential to blues music. You’ll often find them in a 12-bar structure as a part of a long chord progression. These progressions can be written and played in both major and minor keys. While major blues take up the lion’s share of the songs in this genre, minor blues are loved for their somber yet smooth sound. You can use a blues scale to solo over both major and minor blues.

Since this is a list of minor progressions, I am going to zoom in on the 12-bar blues in minor keys. Let’s look at the most basic 12-bar blues progressions: i – i – i – i – iv – iv – i – i – v – iv – i – V. There are four chords in this sequence. The i, iv, and v are minor 7th chords. Meanwhile, the V chord remains a dominant 7th chord, as the chords in any major blues progression. The 7ths makes the sequence sound a lot bluesier than if it were played straight.

Let’s take the example of a minor key to understand this better. In the key of A minor, these four chords are Am7, Dm7, Em7, and E7, making the 12-bar minor blues progression Am7 – Am7 – Am7 – Am7 – Dm7 – Dmy7 – Am7 – Am7 – Em7 – Dm7 – Am7 – E7. There is no dearth of variations in blues, and we’ll explore a more widely used form in the next example.

Popular Songs That Use This Progression: “Life is Hard” (Johnny Winter).

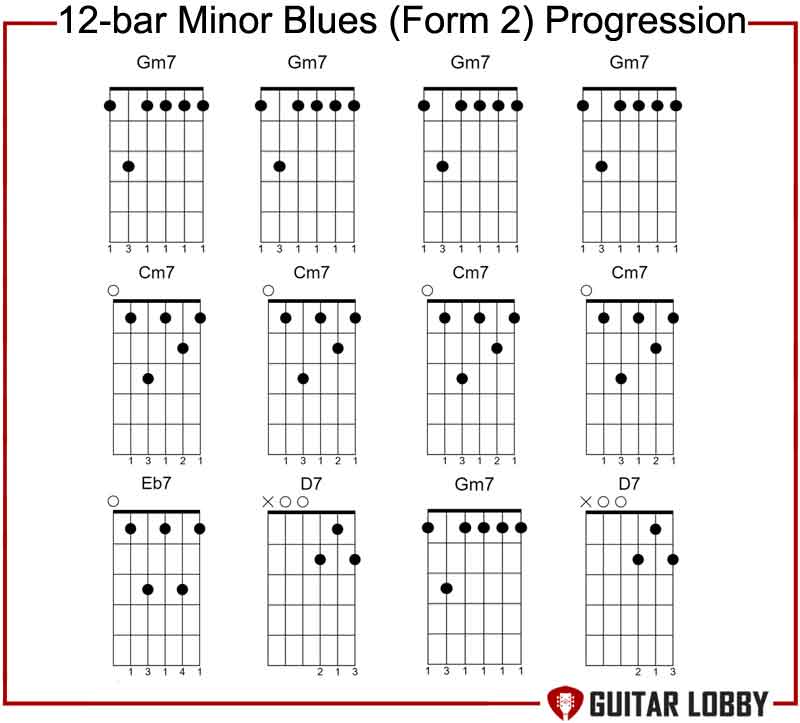

13. 12-bar Minor Blues (Form 2) Progression Variation i – i – i – i – iv – iv – i – i – VI – V – i – V

This minor blues progression is more common than the previous form. You can hear it in several jazz and blues standards, including “Equinox” by John Coltrane and “The Thrill is Gone” by B.B. King. As far as the structure goes, it’s not very different, sharing three of the four chords with the earlier sequence. You still have the i and iv minor 7th chords and V dominant 7th. What’s different here is the VI chord, which is another dominant 7th.

The new 12-bar progression in its entirety is i – i – i – i – iv – iv – i – i – VI – V – i – V. Notice how, till the 8th bar, this sequence resembles the earlier one. The only change is in the 9th and 10th bar, with VI going to V.

We used the A minor key in the previous form. So, let’s apply this progression to another key, say G minor. The four chords would be Gm7 (i), Cm7 (iv), D7 (V), and Eb7 (VI). Our 12-bar minor blues progression would become Gm7 – Gm7 – Gm7 – Gm7 – Cm7 – Cm7 – Gm7 – Gm7 – Eb7 – D7 – Gm7 – D7. These progressions sure look scary, but break them into three parts and four bars each, and it’ll be easier to master.

12-bar minor blues add intensity and emotional depth to a song. Every aspiring blues guitarist should devote time to learning minor blues in addition to major progressions. Once you have the basic forms down, you can use the blues scale to improvise over them.

Popular Songs That Use This Progression: “The Thrill is Gone” (B.B. King), “Birks Works” by Dizzy Gillespie, “Long Train Running” by The Doobie Brothers.

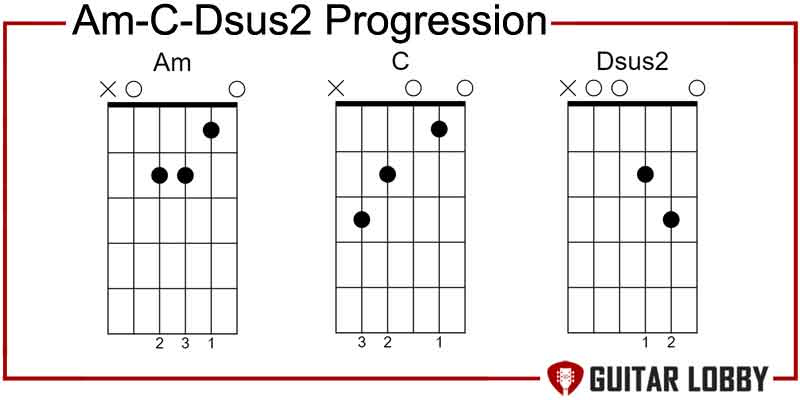

14. Am – C – Dsus2 Progression i – III – iv

Nine Inch Nails’ industrial rocker “Hurt” got a heart-wrenching makeover by Johnny Cash. His version was a melodic and introspective, sparsely arranged country song. But both tracks share a stunning three-chord progression in a minor key: i – III – iv. The sequence is set in the key of A minor. You must be well acquainted with the chords in this key by now. The ‘i’ chord is obviously Am. Meanwhile, the III chord is C.

The pickle is the iv chord which, in this case, should ideally have been Dm. However, I’ve shared many examples in this list where songwriters venture beyond the key using notes and chords from parallel scales. So, in this song, we see Dm getting replaced by Dsus2. This is a suspended chord and doesn’t have a third. So, you can neither categorize it as minor nor major.

If you look at it closely, you’d realize it’s like the classic i – iv chord progression, except with a III chord wedged between. Another thing worth mentioning is the III and iv chords are played together in one bar. So, the correct way of looking at this progression is i – (III – iv).

Popular Songs That Use This Progression: “Hurt” by Nine Inch Nails, “Hurt” by Johnny Cash.

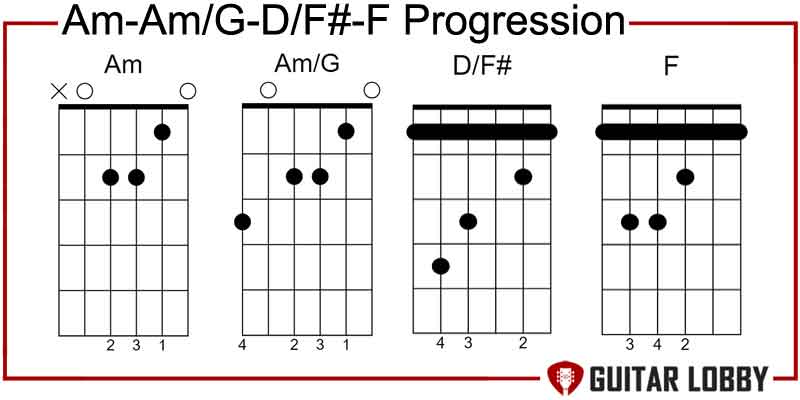

15. Am – Am/G – D/F# – F Progression i – i/7 – IV/b4 – VI

George Harrison’s most memorable contribution to the Beatles’ discography, “While My Guitar Gently Weeps,” is packed with beautiful and powerful chord progressions. 12 of them! But one of the most recognizable sequences in the track is i – i/7 – IV/b4 – VI.

Don’t be alarmed by the way it looks. It actually has a descending bassline built into the chord progression to add an element of melancholy and suspense.

But first, let’s look at this progression in the simplest way possible as i – i – IV – VI. The song is set in the key of A minor. So that makes the sequence Am – Am – D – F. We know by now that A minor doesn’t have a D major chord, only D minor. So, where has the D chord come from? Again, there’s been a bit of borrowing, this time from the A melodic minor scale.

Apart from the way it sounds, the reason why Harrison probably used a D chord here is for the D/F# chord to accommodate the descending bassline of A – G – F# – F.

Popular Songs That Use This Progression: “While My Guitar Gently Weeps” by The Beatles.

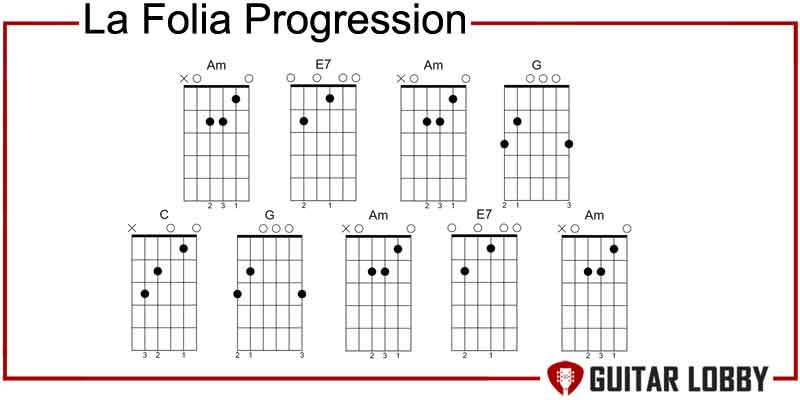

16. La Folia Progression i – V – i – bVII – bIII – bVII – i – V

You’re looking at the most enduring chord progression in Western classical music, La Folia. These triple-meter sequences originated in the late 15th century and dominated the Baroque era. They were originally used for fast, energetic dances and were either set in the key of D minor or G minor.

Having been around for centuries, Folia has undergone a series of transformations. There’s more to it than just chord progression. Think of Folia as the whole package with chord sequences, rhythm, melody, meters, and patterns. But I’ll only be focusing on the minor chord progression for now.

Though there are many versions, the early Folias are said to have started with an accent on the dominant ‘V’ chord with either a major or minor tonic chord, while the later ones had a minor tonic chord. The most common group of Folia chords are i – V – i – bVII – bIII – bVII – i – V.

In the key of A minor, this sequence becomes Am – E7 – Am – G – C – G – Am – E7 – Am. The harmonic structure reminds me of a standard 12-bar blues progression. Like the blues progression, La Folia is also great for soloing over. But unlike the 12-bar blues, the medieval chord progression exists in two 8-bar phrases.

Popular Songs That Use This Progression: “Force Majeure” by Tangerine Dream, 1492 Movie Theme, The Addams Family Soundtrack.

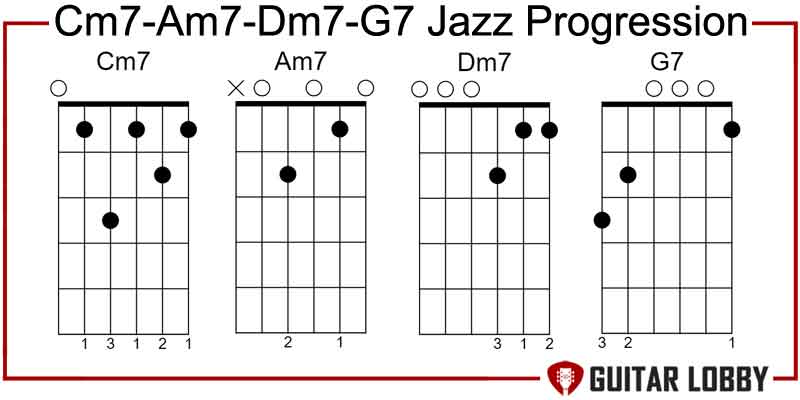

17. Cm7 – Am7 (b5) – Dm7 (b5) – G7 Jazz Progression i – vi – ii – V

The 1 – 6 – 2 – 5 is a popular progression in jazz and gospel, especially in its major form” I – vi – ii – V. You’ll find it in several jazz standards and also a part of “Rhythm Changes” – a 32-bar chord progression in Jazz based on George Gershwin’s “I Got Rhythm.” Although it doesn’t deliver as much resolution as the more famous 2- 5 – 1, the 1- 6 – 2 -5 is an essential chord sequence worth learning when it comes to jazz.

Mastering its minor form offers great grounding in jazz soloing in minor keys. In the key of C minor, this sequence looks like Cm7 – Am7(b5) – Dm7(b5) – G7. As far as the tonality goes, it sounds mysterious, dark, and also a little bluesy. Jazz guitarists also use this progression as a turnaround. A turnaround is a chord progression that returns to the I or i chord. Turnarounds and their variations are the bread and butter of jazz.

When you play it, you’ll notice the chord qualities of this progression is different from its major form. It’s also more challenging to play with two half-diminished chords. Also, since it’s a cyclical chord progression, beginners might find it trickier to master in comparison to, say, more straightforward primary chord ones like i – iv – v. But it’s totally worth the effort if you’re eager to add some iconic jazz and blues tunes to your repertoire.

Popular Songs That Use This Progression: “Softly As in a Morning Sunrise” by Chet Baker.

What Makes a Chord Minor?

A chord is made up of multiple notes played simultaneously. While a major chord utilizes the 1st, 3rd, and 5th notes of a major scale, a minor chord contains the 1st, lowered 3rd, and 5th notes of the scale. So, it all boils down to the 3rd note, which is flattened by one fret.

Major = happy; Minor = Sad – Raise your hand if you’ve been taught this common hack to differentiate between the two chords. There is some truth to it. Major chords sound brighter and uplifting in comparison to minor chords, which sound dark and cynical. Want to know why? Then, let me take you through the basics of scales.

Understanding the Various Minor Scales

A scale, regardless of major or minor, is made up of seven notes, starting with the root note. Each note is one note higher than the previous. In the case of a major scale, say the A major scale, the notes would be:

A – B – C# – D – E – F# – G#

Play these notes on your guitar, and you’ll notice how bright and uplifting the sound is. The minor scale is different, with the 3rd, 6th, and 7th scale degrees flattened by a semitone. So, the A minor scale would have the following notes:

A – B – C – D – E – F – G

Now, play the notes one after another. Don’t they sound melancholic and mysterious vs. their major counterparts?

There are various forms of a minor scale, and the one we just saw is the natural minor scale. The other two are the harmonic minor scale and the melodic minor scale.

The natural minor scale is the easiest one to tackle because it doesn’t stray from the signature key. Meanwhile, the harmonic scale has a sharpened 7th note.

A – B – C – D – E – F – G#

The melodic minor scale is the trickiest of the three, with an ascending and descending form. The ascending scale has raised 6th and 7th notes: A – B – C – D – E – F# – G#. Meanwhile, the descending melodic minor has lowered 6th and 7th, making the notes in the scale A – G – F – E – D – C – B.

Understanding these scales and their different versions is important for aspiring guitarists and musicians to get a good grounding in songwriting. You’ll also notice most songs use chords in the harmonic minor and melodic minor scales rather than sticking to just the natural minor scale.

What is a Minor Chord Progression?

A chord progression is a group of chords that flow in a particular sequence, giving a song its foundation and direction. To understand what makes a progression minor, we need to talk about the chords in a minor key.

Chords are typically represented by Roman numerals, with uppercase numerals denoting major chords and lowercase ones indicating minor chords. These numerals also represent the scale degree of a chord and show the chord quality.

Based on what we discussed in the previous section, here’s a quick look at the chords you’ll find in a minor key

i – ii˚ – bIII – iv – V – bVI – bVII

The scale progression starts with a minor chord, followed by a diminished chord, then a major chord, followed by two minor chords, and ends with two major chords. The ‘b’ indicates flattened chords built off the altered degrees of the scale (Remember, 3rd, 6th, and 7th notes are lowered in a minor scale).

Now, let’s take the example of the C minor key to find its associated chords.

Cm – D˚ – Eb – Fm – Gm – Ab – Bb

A minor chord progression must have chords built off notes of a minor scale. In other words, minor chord progressions are in minor keys. They evoke different emotions in listeners, making a tune brooding, poignant, and bleak compared to bright and cheery major chord progressions.

Why Makes Minor Chord Progressions an Important Songwriter’s Tool?

If you’re looking to write a song aimed at evoking nostalgia, a sense of suspense, and wistfulness in listeners, you can’t go wrong with minor chord progressions. Take Johnny Cash’s “Hurt,” for example, or “Back to Black” by Amy Winehouse – I shudder to imagine what they would’ve sounded like with major chord progressions.

Sure major chord progressions are way more popular, but minor chord sequences help in conveying a lot with less. You don’t have to rely on unusual chord shapes and complex techniques to accompany your song’s powerful message. A chord progression in a minor key would do the trick.

But expressing sadness and melancholy isn’t all that these chord progressions are good for. There are plenty of famous tracks that challenge the sadness stereotype. We’ve got the uplifting “Sultans of Swing” by Dire Straits and Nirvana’s angsty “Smells Like Teen Spirit” and the smooth and funky “Californication” by Red Hot Chili Peppers.

Wrapping Up:

These progressions can add a wide range of emotions and plenty of depth to your playing. You could start by mastering the simpler ones like the i – iv – v or i – VI – III – VII before attempting the more complex 12-bar minor blues or jazz turnarounds. Once you’ve picked up a few, why not write your own progression? The simplest way to do this is to choose a minor key and a bunch of chords in that key and finally strum them on your guitar.

My name is Chris and I’ve had a passion for music and guitars for as long as I can remember. I started this website with some of my friends who are musicians, music teachers, gear heads, and music enthusiasts so we could provide high-quality guitar and music-related content.

I’ve been playing guitar since I was 13 years old and am an avid collector. Amps, pedals, guitars, bass, drums, microphones, studio, and recording gear, I love it all.

I was born and raised in Western Pennsylvania. My background is in Electrical Engineering, earning a Bachelor’s degree from Youngstown State University. With my engineering experience, I’ve developed as a designer of guitar amplifiers and effects. A true passion of mine, I’ve designed, built, and repaired a wide range of guitar amps and electronics. Here at the Guitar Lobby, our aim is to share our passion for Music and gear with the rest of the music community.